Every once in awhile a game really grabs our attention. I’m not even going to mention the game that has actually broken this camel’s back, if only to not fuel my inevitable detractors. But I will just simply state, as fact, that occasionally a game comes out that gets so much attention in one way or another that it creates first a bubbling discussion, then a ribald debate, and, finally, a hipster ostracization wherein snooty bloggers and podcasters won’t even mention the game’s name in a post.

Clearly, I’m above all this.

One Thing to Remember

I want to start by asserting one simple caveat. If you take nothing else away from all the writing I ever do about videogames, please accept and respect this:

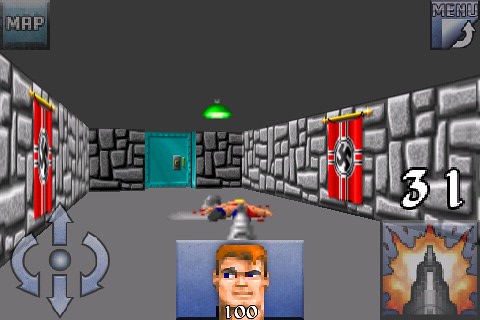

ALL GAMES ARE ART

Without qualification or exception, every single game that has ever been created is art. Art. ART. It does not matter what authorial intention is/was. It does not matter what consumer or critical reaction is/was. It is just a fact that every game ever created, and every game that will ever be created, is art, is artistic, is artful.

Every little thing that we as humans have created or ever will create is ART. We cannot pretend like we live in a world where Art inhabits a little petting zoo for the rich and privileged. Nor can we pretend like there is some committee or expert who can unequivocally declare a work “art” or “not art.” It is a challenge of quantum complexity and insane futility to proceed down a path that presupposes only certain things are or are not art.

Any time an individual speaks about something being “artistic” I do not read that as an argument. I read that as a personal judgement about the quality of the individual’s experience, something that is specific to a particular context, informed by a unique history of contexts.

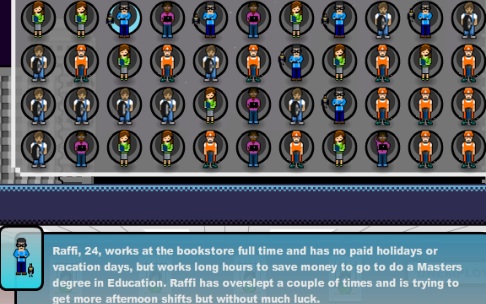

Sturgeon’s Law + $$$ = Videogame Industry

In the gaming industry of the early 21st Century, Sturgeon’s Law is in full effect. While all games are art, they are not all “good” art. So the trick becomes to learn about the landscape of games, to examine every single game that comes out and to know what makes a game “good” or “bad” and, most importantly, why a game has that effect in a given context. It must be understood that every game must be discussed within a specific context. Contexts may be able to mix, but ultimately no one discussion of any game is going to suss out all of the interesting things to say about that game. And a game which rates very well in one context (say, the “Played while getting drunk with buddies” context) may be a real stinker in another context (for example, the “Played with wife and kids on family games night” context).

It is pointless to believe that any one discussion is enough for any given game, regardless of how “good” or “bad” that game is considered.

It is also important to remember that most games try to push the easiest-to-reach buttons. This is what gives most game plots their melodramatic flair. Mainstream blockbuster games are very much like mainstream blockbuster movies in that they are typically designed to offend as few people as possible and trace simple plotlines enacted through predictable character behaviors with very little emotional motivation. At best we get a game of Spielbergian qualities, which, unfortunately, much of the pubic is happy to brand “artistic success” and “legitimate consumer entertainment.”

But why should games be different from any other media form? I enjoy complex characters, motivational quandries, and intricately woven stories in my books, poems, movies, television shows, music, and comics. I enjoy media that asks me to figure out something about how it works. Why wouldn’t I look for those same qualities in the games I play?

I appreciate small movements as much as large movements, but small movements of concept, gameplay, or narrative do not illustrate well in a quick press release or five screens among a hundred other articles. In order to understand what is “good” or not about a game, we must examine it in depth. However, the industry is geared around the latest and greatest. It has only been in this latest generation of consoles and downloadable game services that old games were reconsidered as viable play options. But gamers know that a good game can be rewarding for years. This has been a constant tension, but I feel like gamers are finally beginning to turn the tide.

We can slow down. We can appreciate the full quality of the games we play. We can appreciate the way that context changes over time, which affects our understanding of a game. We can resist what may be the most insidious easy-button the game industry has in their back pocket: innovation.

The Myth of Innovation

When talking about easy-outs for game developers and publishers, novelty is the easiest of them all. “Innovation” has long been a mantra for the games industry, and on one hand, innovation must and will inevitably continue. It is impossible to deny that the growth of gaming is tied to the growth of technology. New tech has allowed us to realize just how important playful activity is, and games have grown as a media form to fill that niche. As technology progresses, it is unavoidable that games will utilize new tools to provide new experiences (or to rehash old ones). But, on the other hand, innovation is also one of the least useful measures of a game’s quality.

Given that innovation is a requirement of environmental success, how can it be such a commonly used term when determining if a game is “good” or not? Isn’t some level of innovation always expected? Isn’t some level of innovation often dictated by middleware tools and decisions made by hardware manufacturers? And do those “innovations” often push developers, willingly or not into new territory, forcing innovation with complete disregard to authorial intent? Yes. This is how innovation works in the industry — as often as not at the demand of a zaibatsu, not the whim of a developer. And here we remain, with an industry that creates new tools every day, yet has no problem re-releasing Product A as Product A 2: Now With 5 More Guns! and often receives critical acclaim for doing so.

It’s sad that game developers who recognize and respond to the environmental pressures of innovation, and keep in mind all the other things that make a game good, are not always the most successful. Because innovation is not really desired by most audiences (cf. the current state of Hollywood or prime time television), the really innovative stuff is often not appreciated until it has been done a few times. The most successful mainstream game publishers and developers are scavengers of the landscape, adept at picking the bones of better games and then polishing those bones and presenting them as sanitized, crowd-friendly experiences for kids and adults who don’t really want to think much about their games. And all of that happens under the banner of innovation.

One Game Proves Nothing

In short, innovation is a hollow claim to greatness, and any one standout game is not going to be enough to convince anyone of anything. I’m still not sure exactly who we’re trying to convince, or what we’re trying to convince them of. But it seems like we all want our parents to be proud of us, and in some way that means getting them to respect videogames. And I suspect more people would like their bosses to like videogames, too. And then there is that tricky “art” thing, which I feel like I laid to rest several paragraphs ago.

It probably comes down to the simple fact that when you like something, you want to share it. And people who “get” videogames tend to really enjoy them. I appreciate the different “games as art” or “this game is art” discussions because they achieve two things: 1) They get people talking in depth about games, which is something we need. 2) Participants in these discussions reveal a lot about themselves and why the games they play resonate, and those revelations are often endearing and fascinating. Don’t forget dear bloggers and podcasters that to all the rest of us, you are the NPCs in this game of life.

But any individual’s estimation of any game is never going to be representative or true. So no matter how many game critics clamor for a title, or how many fanboys petition for a sequel, nothing is going to change in the game industry or in how games are perceived in our culture until there are a lot more good ones. We have not even begun to see the game explosion; we are still in the infancy of the form.

Don’t give me one good game. Give me one thousand good games.

Give me enough good games to convince all my friends to play. And enough to convince the people I hate to play. And give me enough good games to convince my company to make games. And enough to get parents to buy games for their kids. And give me enough good games affecting enough kids for teachers to recognize the benefits. How many games is that? And over how many years?

I think it will be a long time before we don’t have to talk about games as art, or arts as game, and I intend to enjoy every discussion along the way.

Alexander has been posting and tweeting all week from the Electronic Entertainment Expo in Los Angeles. Among her impressive amount of info-relay is this column up over at GameSetWatch, in which she makes the argument that Electronic Arts’ upcoming video game Dante’s Inferno need not worry about trying too hard to adhere to its literary namesake. In describing the game as an “action title set in Hell,” Alexander asks a certainly appropriate rhetorical question: “Why not have fun with it?”

Fun is almost always the baseline value by which we evaluate something we might call a “video game” (tangentially: if you want to get really semantic about this term, check out the latest episode of Big Red Potion, where Sinan Kubba, Joseph DeLia, Eddie Inzauto and yours truly get into some interesting territory about what we might mean or assume when we use that particular word). By nature, we are creatures who prefer the warm fuzzy over the cold prickly, and activities which require us to focus for long stretches of time and draw more than summary conclusions about what we’ve experienced are made more difficult when we aren’t having a pleasant time doing them.

Games and fun might go well together like chocolate and peanut butter, but let’s be careful not to assume that these aren’t incredibly subjective things we’re talking about. And yes, I know all of this nit-pickery about terminology can get incredibly tedious and annoying, but these acts of definition are nevertheless important, because when we talk about games as a medium, we are essentially talking about how game designers communicate ideas through building artistic vehicles for those ideas, as well as how game players receive and react to those ideas. When we whittle these efforts down to whether a game is “fun” or not, a lot can get lost in the trimming.

Case in point: Dante’s Inferno. Alexander writes, “The Divine Comedy, after all, is largely a poem about two guys walking and talking, not exactly the core gameplay of an action game. In that way, the liberties the [design] team took were intended to create a stronger video game, a more reasonable priority for, well, a video game, than focusing on a strong epic poem adaptation.”

These “liberties,” Alexander reports, include depicting Dante as “a former Crusader armed with a giant scythe that looks like it’s made out of a monster’s spine,” who embarks upon “a vaguely risque subplot about rescuing Beatrice from the devil’s seduction.” Some of the obstacles blocking this digital Dante’s path include “the imagination of Chiron’s [sic] boat as a living entity with a head to be twisted off at the neck,” and “unbaptized babies running around with weapons.”

“Gleefully gruesome and literally hellish,” Alexander continues, “the game seems to use the poem’s backbone and references to enrich an action game, rather than use the game as an attempt to emulate an epic poem in video game form…Audiences would like a game that uses the medium’s potential to correspond with other cultural sources, and that’s an excellent goal.” She punctuates her astute observation in asserting, “Dante’s Inferno is not that game — it would rather be an action title. And that’s okay.”

I am lockstep with Alexander in seeking out connections video games have to other artforms. I, too, believe that finding the places where these media (“sources”) intersect (“correspond”) is worthwhile. For me, whether a game is “fun” or not is almost always secondary to me deciphering what it might be trying to tell me, and then deciding what I ultimately think about that particular argument, issue, or aesthetic. How “successful” a game is has everything to do with its coherence as an artistic expression and nothing to do with its NDP numbers. For me, games are an interactive conduit for ideas, arguments and meaning, and “action” is that thought, deed or utterance inspired by the experience of playing the game.

So what’s the problem, then? It’s simple: caught up in the never-ending cattle rush among other videogame publishers to acquire and trademark new brands of intellectual property, Electronic Arts have marginalized Dante Alighieri’s Commedia as little more than a crudely-painted backdrop for a yet another insipid action adventure. And as much as I respect Leigh Alexander, I’m not at all sold on the And It’s Okay argument.

Since Electronic Arts’ attention span for Dante’s Commedia begins and ends with Inferno (dare we imagine what its take on Paradise might look like?), it’s important to consider the “recognizable symbology and references” from that particular section of the epic that so-called “literature buffs…[will] still get a kick out of.” More precisely, it’s important to consider those references in their proper contexts. This assumes that we are indeed sincere about finding those places where different “cultural sources” do that “correspond” thing they do; of course, part of the problem is we already know that old colloquialism about what an assumption makes out of you and me.

See, here’s the rub: to even begin approximating the underpinnings of Alighieri’s 14th century text-based adventure, Dante’s Inferno’s executive producer Jonathan Knight would need to conceive and deliver anti-papist imagery so graphic and severe that Dan Brown’s conspiracy theory novels would truly pale in comparison. But this assumes (there’s that word again…) Knight and his development team at Visceral Games (1) understand Alighieri’s justifications for all the savagery depicted in Inferno and (2) actually care about pulling them all the way into the 21st century; on both counts, this could be assuming far too much.

I submit for your consideration this recent interview with EuroGamer’s Kieron Gillen, in which Knight explains:

That he would supplement the “literary experience” (meaning…???) “with fighting” demonstrates a fundamental misunderstanding about Dante Alighieri’s agenda as a game designer. His Commedia—and especially the 33 cantos he called Inferno—is pure agon. It is The Fight itself, given body and force through text. If there is fantasy in Dante’s epic, it is very much a fantasy of the real; if there is insanity, it is only so due to patience and lucidity.

Because here’s the heart of the matter: Electronic Arts would no more have us butcher Boniface than miss their annual Madden ship date. The National Broadcasting Company still has never rebroadcast arguably the most incendiary 9 seconds of live television ever shown in the United States, wherein after performing an a capella rendition of Bob Marley’s “War,” singer Sinead O’Connor tore up a picture of Pope John Paul II and urged everyone watching to “Fight the real enemy.”

httpv://www.youtube.com/watch?v=iYw8JR1N90o

If you thought the Catholic League came unhinged over Kevin Smith’s Dogma, just imagine their reaction to a video game wherein the player-interactor willfullly exacts corporal punishment upon a pope.